I teach a lot of drawing this semester so I think about it more. I come from drawing, I started drawing before painting and I find drawing easier to teach because it has fewer variables and can be a very portable, low maintenance activity.

“Humans create lines wherever they go,” writes the philosopher Tim Ingold. What is a person, he asks, if not a tying together of all the lines they make?

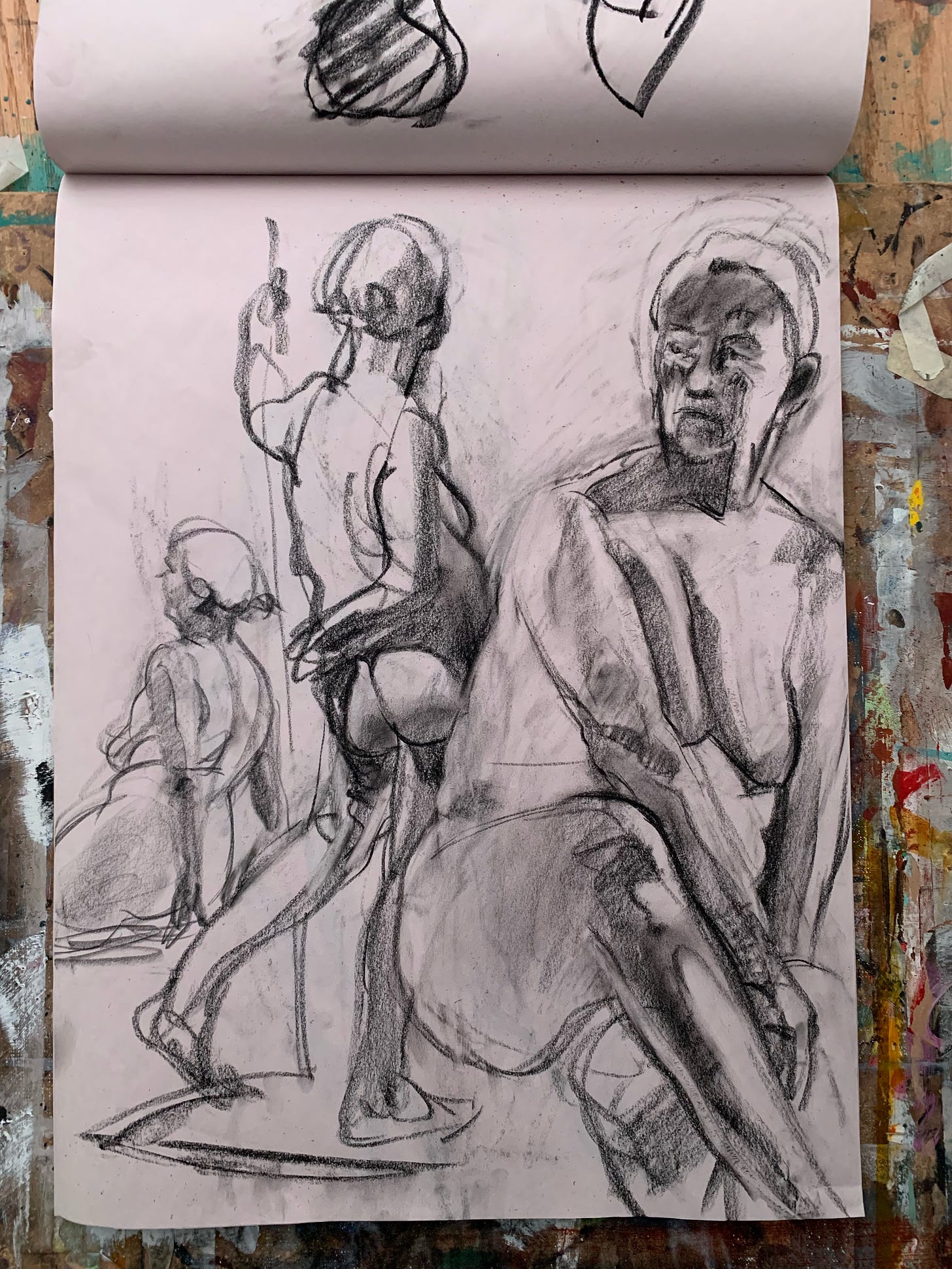

I was recently running a life drawing class when I stopped at one easel and made some changes in a student’s drawing (I must admit that I take great pleasure drawing all over students’ drawings, often to their mortification!) She asked me a profound question:

How do I see what you are talking about? I see it when you show it to me, but when I look, I don’t see that.

This got me thinking. Indeed, drawing from observation is first about seeing. You need to see things in a certain way to then be able to draw them. This is especially true if your goal is to make drawings which convincingly represent the three dimensional world that we see around us. The first complication is that you are trying to talk about three dimensions onto a two dimensional surface.

I think one problem is how we normally look and what we see. Our eyes move around almost of their own volition capturing information about our surrounding environment constantly. We don’t consciously think about the act of looking and seeing. This visual information forms a kind of checklist related to what we need from the environment at the time. It could be on the level of: I am hungry, what is there to eat? Apple, cheese, cracker. The apple is red. Maybe it has a bruise. It is edible. The cheese is hard or soft and it is white or yellow or rotten. It stinks. But is it bad? Is it edible? Hard to tell with cheese sometimes.

This kind of information is fairly surface based, but sufficient for daily life and the avoidance of food poisoning. It translates into the mind as simplified visuals, signs or icons for apple in general and cheese in general. Of course, we can recognize a huge variety of cheese and apples and we can notice the subtle differences in texture, colour and other attributes. But how do you draw that, beyond icons for different types of cheese? How do you draw the one-of-a-kind appearance of the three dimensional subject onto a flat piece of paper?

Without some training, you probably will not think about how light plays differently on the surface of an apple or a cheese. How light reveals that a surface is shiny, matte, rough, transparent or reflective. Or that the apple and cheese are both objects with three dimensions. You know this to be true because you constantly encounter the world in all its dimensions and your mind knows this. So you take it for granted. You might not pay attention to the varying intensity of shadows and how they can be deceiving: shadows can either cancel or emphasize the fact that an object occupies space and has volume. The same can be said about light.

When you have to draw, what you need to notice has nothing to do with edibility or danger or even beauty. It has nothing to do with how your mind “knows” what an apple or a cheese looks like - those are symbols. It has everything to do with noticing how light makes things visible or invisible. How shadows are formed in response to a surface turning away from the light. There are different approaches to drawing and observational drawing is about the eye, what it looks for and what it sees. To make better observational work, you need to forget that you are drawing whatever it is you are drawing. Do not draw an apple or a cheese or a chair or a portrait. You need to practice looking very carefully for shapes that delineate shadow and light areas, the spacing between these shapes, their relative value, whether they overlap or block each other and so on. This is the abstract language of visual art. So, even though you are trying to emulate reality, you need to first see it in a simplified, structural way. I want to write about the other types of drawing in future posts but for now, I can recommend to you some further reading on this subject.

The Natural Way to Draw by Kimon Nicolaides is a book that I used when doing life drawing at Sheridan college in the 1990s. It’s just a great read about drawing and seeing things in a certain way. It also starts with the premise that anyone can draw, there is no special talent required. The author was a sculptor so his method is based in understanding 3d forms and then drawing them. Most great sculptors are also excellent drawers. The book is a program of study - it provides a one year intensive recipe for you to learn how to draw. I have met people who have done it and were very pleased with the results. Check it out for yourself.

If you’ve seen Ways of Seeing, then you know that John Berger is a very compelling writer who’s had a life time fascination with seeing and drawing.

For the artist drawing is discovery. And that is not just a slick phrase, it is quite literally true. It is the actual act of drawing that forces the artist to look at the object in front of him, to dissect it in his mind’s eye and put it together again

- John Berger, Drawing is discovery

Check out Berger on Drawing

Finally, a perennial favourite and a great doorway into observational drawing, is Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain by Betty Edwards. This book really breaks down the type of abstract looking that is necessary for good drawing.

What are your thoughts on all of this? What does drawing mean to you or how do you think about the act of drawing?

Nicolaides is very observationally based. I found that observation didn't really work for me until I started learning the topology, relative proportion, and functional connections of the human body; that is, drawing more or less constructively.